|

FEBRUARY 2010

A classically trained pianist and graduate from the Toronto Conservatory of Music, veteran film composer Paul Zaza has a resume listing over 175 feature films, television episodes, specials and documentaries under his belt in a career spanning three decades.

A recipient of the prestigious Genie Award as well as numerous SOCAN awards, Zaza creates compositions that often blend conventional orchestral sounds with his own unique style, including synth and cooked, harmonized effects. From a genre standpoint, his works have run the gamut from comedies, to drama, to thrillers, to action films.

His signature music - the 'Zaza sound' - has enlivened more than a handful of well known horror classics, including Bob Clark's upscale thriller Murder by Decree (1979), Paul Lynch's original slasher Prom Night (1980), and George Mihalka's gorefest My Bloody Valentine (1981).

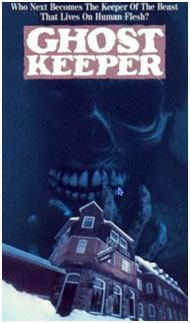

His horror credits alone go on and on, including moody, experimental music for snowy terror fare like Ghostkeeper (1981) and Curtains (1983), cues for the Canadian sleaze-giallo American Nightmare (1983), as well as all three Prom Night sequels. His horror credits alone go on and on, including moody, experimental music for snowy terror fare like Ghostkeeper (1981) and Curtains (1983), cues for the Canadian sleaze-giallo American Nightmare (1983), as well as all three Prom Night sequels.

In addition to sitting down with us and discussing his lengthy and illustrious career, Zaza also graciously provided exclusive cues from some of his most seminal horror scores.

The Terror Trap: When did you first know you were interested in music?

Paul Zaza: Around the age of four. Because that’s when I had my first piano lesson. My dad had an old beat up piano in the basement. And as a kid, I wouldn’t stay away from it. I kept plunking out little melodies I heard on the radio. We didn’t have much television.

The odd little tune that I heard, I would repeat it on the piano. My dad was impressed with this little two-year old kid crawling around and playing melodies on the piano. When I was four, he took me to see a very good music teacher here in Toronto. And the teacher said, “Well, he’s kind of young. I don’t usually do kids this age.” But he gave me an ear test and then agreed to start me. It’s not something that I ever really thought about - it was just in my blood.

TT: You attended the exclusive Toronto Conservatory of Music?

PZ: Yes. The faculty of music. Which is pretty much joined at the hip with the University of Toronto music department. In fact, that’s where my dad took me. It was right to the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. And he got the best teacher. This guy was a PhD in music. Dr. Dolan, who was my mentor. He was more like a father to me because I knew him ever since I was a kid. I studied with him for some twenty years.

My dad said, “I want the very best.” He didn’t want to just take me to some guy down the street who was teaching music lessons in his spare time.

So that’s where I started at the age of four. At the Royal Conservatory. And I stayed there and ended up getting the degrees and all the papers and everything from the same place I started. I never changed. So that’s where I started at the age of four. At the Royal Conservatory. And I stayed there and ended up getting the degrees and all the papers and everything from the same place I started. I never changed.

TT: Tell us about touring with the Fifth Dimension.

PZ: That was a fortuitous little happening in my life, where a gift landed on my doorstep. I happened to be the bass player in a theatre production of Hair in Toronto, which was a huge hit that played for about 2 1/2 years. It was the perfect job because I did the show at night and went to school during the day.

I knew the music really well, and the Fifth Dimension came to town for a sellout show at the CNE (Canadian National Exhibition) Stadium. As bad luck would have it for them, their bass player ended up in the hospital. The bass was very important to the group’s sound. My name came up, and I went down and rehearsed and did a show with them.

After the show, their manager invited me to go on tour with them for three weeks. The three-week tour became a two-month tour all over the United States. I made a huge amount of money. It was weird because I was the only white guy on the stage, including the roadies and the stagehands.

TT: And your love of music eventually led to your career in film scoring?

PZ: The whole segue into film music was a fluke. I never dreamt of being a film composer as a kid, or as a teenager. Like every other teen, I wanted to be in a rock band. You can imagine..

TT: Sure.

PZ: I wanted to be a world famous rock star. And film music was not something the average kid thought about back then. Today they do. But back then, film composers were “old guys” like Bernard Herrmann. It didn’t have near the glamour that it does today.

The paradigm has shifted a bit in that regard over the last, say, thirty years. Nowadays, I get emails, letters, phone calls from kids in their early teens - who all want to be a famous film composer. The paradigm has shifted a bit in that regard over the last, say, thirty years. Nowadays, I get emails, letters, phone calls from kids in their early teens - who all want to be a famous film composer.

So, I had a recording studio at the time. And one of my clients was a film composer who booked my studio to record a film score he was hired to write. I won’t name names, and I won’t name the film, because that’s just not an ethical thing to do.

But the long and the short of it was, he screwed it up and the director was sitting there, very upset because his budget was blown and he ran out of time and money.

This composer - who was quite well known at the time - just totally missed it. He didn’t get what the director wanted, musically. And I happened to be there, and was very hungry for the experience and work.

TT: You were a recording engineer at this point?

PZ: Yes. I had a recording studio and I was an engineer. I was a musician. I wasn’t really a composer. I knew a lot about music but I didn’t really have any expertise in film scoring. It wasn’t something I had ever even thought about.

But the interesting thing was, we had a little projector set up and I saw the film. I saw what the scene was. I heard what the composer did, and I actually understood what the director’s dilemma was. So I stood up and said, “I can fix this. I know what you want. I can do it.”

TT: What was the director’s reaction?

PZ: He said he didn’t have any time, any money left. But I said it was all right. I could do it.

TT: So it was less by design, more by default?

PZ: Absolutely. It was just one of those things where I saw an opportunity and I ran into it. I thought I’d figure it out later. It was a fairly high profile project at the time, and I thought something good could come of it if I could make it work. I had to make it work. So I stayed up a few nights and figured it out. And I did it.

The director was delighted and happy, and I ended up doing his next four feature films. And suddenly, I was on the map.

It’s like so many things in the entertainment industry. Sometimes, you start out going a certain direction. Then you take a right turn that you never planned on taking. And you end up somewhere totally different than where you set out to go. But it’s not that bad. It’s like so many things in the entertainment industry. Sometimes, you start out going a certain direction. Then you take a right turn that you never planned on taking. And you end up somewhere totally different than where you set out to go. But it’s not that bad.

TT: In terms of other film composers, who influenced you and who do you respect?

PZ: Ennio Morricone. Bernard Herrmann. Pino Donaggio. John Williams is one of my all-time favorites. More recently? Alan Silvestri, who I think is brilliant. All of them are very talented. And their work is well appreciated all around the world.

TT: Technology has changed so much over the past three decades. And presumably, so has the process by which you score film music. Take us back to those years - the late '70s, early '80s. How did the process of recording work and what were the steps involved in that process?

PZ: It worked in a very tedious, time-consuming way. There were no samplers. Nowadays, you can take a note from a violin, sample one note, and then with the computer’s help, you can play anything on the violin from just that one sample.

Think of it as if somebody cloned a cell from you and created another you. It’s really quite an amazing process. It has its drawbacks and limitations, of course, but generally, sampling allows the composer or any musician to take just a small sample and make anything out of it.

TT: So no sampling back then?

PZ: No, we didn’t have anything like that. At the time, that was something you read about in sci-fi magazines. Like flying saucers.

TT: What about the logistics? Would you actually watch a film and then compose to it?

PZ: In the very early days, there were no videotapes. You would actually get a 35mm copy, what we called a "work print." And you would play it on a moviola or a little projector. And you’d roll the film, and you’d time it out. PZ: In the very early days, there were no videotapes. You would actually get a 35mm copy, what we called a "work print." And you would play it on a moviola or a little projector. And you’d roll the film, and you’d time it out.

You would look at the scene and you’d say, “Okay, I think this needs a cue that’s gonna be a chase with violins, percussion, bass and piccolo.” And then you write it all out, and have clicks and bar measures.

And you’d time it all out so that at this point on the manuscript, you knew the lead guy was gonna jump out of the window of the car, or whatever.

It was all clicked and time measured out. We had it measured in frames per beat. We had all the tools to allow us to put the headphones on and hear this click, which was like the radar. As long as you were with the click, you knew that, at say, four bars and two beats, that’s where the guy jumped out the window.

Then you would write it out, score it and orchestrate it. And then you’d have to give it to the copyist, who would make all the individual parts for the musicians to sit and play.

You would then book the studio and the musicians. And the copyist would bring the copied parts to the studio in time to put in front of the musicians on the music stands. The engineer would come in and you would explain to him what you were doing. You would rehearse the cue first. Sometimes, we’d roll the picture with it.

You have to appreciate that at this point, this is the first time the director or the producer would have ever heard what you had created. The only other way to do it would be to sit him down at a piano and kind of plunk it out…

TT: So the first time the director and/or producer is hearing your music, it's synched up to the actual movie itself, to the specific scene you composed it to?

PZ: Right. But by then, it’s almost too late. Because if it isn’t right, how are you gonna change thirty musicians right there, on the spot? PZ: Right. But by then, it’s almost too late. Because if it isn’t right, how are you gonna change thirty musicians right there, on the spot?

So there was a certain gamble involved. And that’s where the composer I talked about earlier made a mistake. He had all the musicians sitting there when they realized it was totally wrong…but it was too late to do anything. You can’t re-write a cue while thirty guys are sitting there.

TT: How did you hook up with fellow composer Carl Zittrer, and what was your involvement on Black Christmas (1974)?

PZ: I had hooked up with Carl on a record deal in Los Angeles, where we were doing these albums for a small record label. I got to know him. He was sort of the producer and I was the composer/arranger. I did the same kind of packaging for him as I would do for say, Peter Simpson.

Carl had a life long relationship with director Bob Clark. They went to school together in Southeast Florida. So like many kids, after school they went their separate ways. Carl went off to make his fortune in music and Bob went off to become another Alfred Hitchcock.

They didn’t see each other for quite a long time. Probably ten years or so. They fell out of touch, and then I think Bob called Carl out of the blue and said, “I’m gonna make a movie and I need some music.” Of course, he didn’t have any money. (Laughs.) That movie turned out to be Black Christmas.

TT: Murder by Decree has your classy signature sound. What you and Carl cooked up was very different there from Black Christmas, that collection of atonal sounds and discordant effects.

PZ: Well, Murder by Decree was anything but Black Christmas. It was Sherlock Holmes. It was 1888. Whitechapel, London. It needed real music. Acoustic music. To put an electronic score on that would have been all wrong.

TT: So at that point, Bob Clark knew you from Carl’s work on Black Christmas?

PZ: Yes. He was totally cool with both Carl and myself working on Murder by Decree. His attitude was, “You guys figure it out. Just don’t screw it up.”

Bob’s head was much more into what angle he was gonna shoot James Mason and Christopher Plummer when they’re coming down in the carriage. Or what lens he'd use on the camera when Jack the Ripper is chasing them…that’s what he was worried about.

TT: So you hired a full orchestra…

PZ: Yes. We went to London and hired the Royal Philharmonic. I was scared shitless. This was the biggest thing I’d ever done.

You know, I was a kid in my twenties, standing there and conducting the Royal Phil. I had it all written out - and I crossed my T’s and dotted my I’s and thought, “This should work.” You never know until you put the baton down and you hear the first bar played.

I had the big producers from New York in there, and Bob Clark. There were ninety musicians out there and the pressure was on. But I put the baton down and we conducted the first cue - and it was absolutely glorious. It was just beautiful.

TT: It’s probably the most beautiful of all the Zaza scores we listened to as we prepped for this interview. It has a breadth of scope to it. In particular, the music for the closing credits - a theme of sorts for Annie (Genevieve Bujold) in the film - that's a wonderful piece. TT: It’s probably the most beautiful of all the Zaza scores we listened to as we prepped for this interview. It has a breadth of scope to it. In particular, the music for the closing credits - a theme of sorts for Annie (Genevieve Bujold) in the film - that's a wonderful piece.

PZ: Thank you. Yes, it’s really one of the best things I’ve done. And of course, it’s one of the best films Bob ever did.

I went to see Sherlock Holmes (2009) starring Robert Downey Jr. And not only did they borrow some of the music from Murder by Decree, but they also used some of Bob’s original directions. Some of the sequences like the horse-drawn carriage in slow motion. Almost frame for frame, incredibly similar in this new movie.

TT: Does it frustrate you to see that?

PZ: No. No, it’s a very flattering thing. They must have loved what I did so much they brought it to the attention of the composer. I’ve been on the other side of that. It really is a cesspool of plagiarism that permeates the industry.

TT: How many collaborations did you have with Bob Clark?

PZ: Easily two dozen. Now, having said that, some of them were awful. Some of the films that Bob did, he would be the first one to not want to talk about them if you brought them up. Like Rhinestone with Stallone and Dolly Parton.

TT: Although strangely, none of the horror films he did were turkeys. Each of them seemed to hit their own unique chord with people.

PZ: That's true. He was really good at it. But he didn’t want to be typecast into that genre. I mean, look at what he did after Black Christmas. He did Murder by Decree, which in a way, was kind of a horror film. But not really. And then he did Porky's, which was anything but a horror film. And then he did A Christmas Story, which again, was anything but a horror film.

Bob was a guy all over the place, in terms of genre. He did do some bad films, but even now, when you watch those…they look pretty good.

He wrote a script that never got made. Carl still has the rights to it. It’s a Bob Clark script that he wrote early, early on. And Carl is now trying to get some interest in the script because it’s really edgy. It’s way out there. It’ll creep you right out if you read it. He wrote a script that never got made. Carl still has the rights to it. It’s a Bob Clark script that he wrote early, early on. And Carl is now trying to get some interest in the script because it’s really edgy. It’s way out there. It’ll creep you right out if you read it.

TT: A horror film?

PZ: Yeah. He did a couple of horror things early on. There was Children Shouldn't Play with Dead Things (1973)…

TT: And Deathdream (1974). The horror flick about the Vietnam vet coming back from the war, and it turns out he’s an undead zombie. Sort of like Death of a Salesman, done vampire style.

PZ: Oh right. But there’s another one too, an early Clark horror film. I’m trying to think what the the name of it was. Some kind of really strange, oddball thing that he actually did get made. But I don’t think it ever saw the light of day in terms of release.

TT: Is Murder by Decree one of your proudest achievements as a film composer?

PZ: I think so. It’s a score that’s very pure and it works. It was one of the few films in which almost everything that I wrote got used. They didn’t change it much. In almost every other film, when the directors and the producers start to get “creative” - they really butcher it up and slice and dice it into tiny pieces. They’ll have a favorite cue and they’ll end up using it twenty-five times in the film.

But Murder by Decree pretty much plays the way I wrote it.

TT: That’s a symbol of how good it is.

PZ: It’s also a symbol of how times have changed. Back then, if something worked and it was good, you just went with it. Whereas now, it’s filmmaking by committee. You get these boards of directors micro managing, everybody has a say in the music.

TT: You won the Genie Award (the Canadian version of the Oscar) for Best Score for Murder. What was that like? Did it open doors for you?

PZ: Canada is a funny place. If this were an Academy Award, my phone would have been ringing off the hook for the next ten years. The Canadian film industry has a very strange attitude. Their attitude is “Oh, he’s too expensive now. We’d better not call him.”

TT: Really?

PZ: Yeah, in fact…I probably noticed that my phone got real quiet after I won the Genie Award and I couldn’t figure out why. But I still managed to drum up some work.

TT: Did you get Prom Night as a result of your work on Decree?

PZ: I don't know. One thing that happened, Murder by Decree became one of the best films of the year. It won awards and I was on national television. And suddenly the film community here in Canada knew who I was. So that didn’t hurt.

But I don’t know if Peter Simpson hired me because I won the Genie, or he liked what I did. Or he just liked me personally. I don’t know. We hit it off when we first met. We really got along.

TT: Tell us about Simpson and your recollection of getting involved with scoring Prom Night.

PZ: Peter was a real meat and potatoes kind of guy. He called it like it is and didn’t mince words. Used a lot of expletives. If he sensed you were selling him a bag of goods, he would just slam the door on your face and kick you right out.

He had absolutely no qualms saying what was on his mind. I dealt straight with him and I was very sincere. I said, “I can do this. If you don’t like it, don’t pay me.”

I just remember him looking at me and saying, “If you fuck this up, I’ll kill you.” I just remember him looking at me and saying, “If you fuck this up, I’ll kill you.”

TT: And you must have met with Paul Lynch, the director of Prom Night.

PZ: I met him. If you directed a film for Pete Simpson, you had a very good chance of getting fired before the film was finished. He almost NEVER got along with any director he hired.

Because typically, the director went for “art"...angles, performances. And Peter was interested in bringing it in on time, and on budget. And if you didn’t, you were outta there.

TT: But his relationship with Paul Lynch must not have gotten as bad as with Richard Ciupka.

PZ: Well, yes, Peter let Paul finish Prom Night. (Laughs.) Richard never got to finish Curtains. Most of the directors never did finish what they started. They were usually let go before we got to post-production.

TT: You’ve spoken about the importance of combining orchestral music in tandem with electronic/synthesizer sounds, especially for horror films. Perhaps the synthesizer was commonly used in many horror films of that period because it was an easy alternative to full-on orchestral realness?

PZ: Well, I used it because I liked all the colors it could add.

TT: The amalgam of the two is what makes your sound unique for these films during that period.

PZ: I still believe this to be true. The real test would be, you’d listen to it and you wouldn’t be able to tell what was what. Was that real, or was that synthetic? It would be the blending of those two different mediums of music that would make it a unique score. It’s evolved so much from those days. PZ: I still believe this to be true. The real test would be, you’d listen to it and you wouldn’t be able to tell what was what. Was that real, or was that synthetic? It would be the blending of those two different mediums of music that would make it a unique score. It’s evolved so much from those days.

To the point that now, someone like Hans Zimmer - who does everything there is now - you can’t tell when you listen to that, if it’s real, or all done on a sampler. That’s how sophisticated it’s gotten.

TT: You wrote all the disco songs in Prom Night?

PZ: Yes, that's correct.

TT: Some casual observations. “Love Me Till I Die” sounds very much like “I Will Survive.” And “Time To Turn Around” is reminiscent of “Born To Be Alive.” Were you influenced by the disco hits of the day?

PZ: I wasn’t. But Peter was.

TT: You mean he told you what he wanted?

PZ: Oh, he did more than tell me what he wanted! He went to the record store. Actually, he didn’t do this himself. He had one of his minions go to the store. And he bought a dozen of the biggest disco hits at the time. Of course, Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” was one of them. And the Patrick Hernandez song (“Born To Be Alive”). PZ: Oh, he did more than tell me what he wanted! He went to the record store. Actually, he didn’t do this himself. He had one of his minions go to the store. And he bought a dozen of the biggest disco hits at the time. Of course, Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” was one of them. And the Patrick Hernandez song (“Born To Be Alive”).

So he bought the current biggest disco records from the store, and he puts these songs right in the movie itself. Paul Lynch actually shot those sequences to those hit records.

TT: Oh?

PZ: Absolutely. Here’s what happened. The songs were in Prom Night, and there’s one scene…I think they cut it out…but the actress is even mouthing the words to “I Will Survive.” You could see her mouth!

TT: Hah!

PZ: And in Peter’s unique style, he said, “Well, we’ve got these songs and this will be great, because these are big hits and will make the movie more successful.”

So he had his legal people go buy the rights, and as soon as they got on the phone with the record labels for say, Gloria Gaynor’s song, the usage people wanted something like $300,000 - which was a third of the movie’s budget. So he had his legal people go buy the rights, and as soon as they got on the phone with the record labels for say, Gloria Gaynor’s song, the usage people wanted something like $300,000 - which was a third of the movie’s budget.

And then of course, the more calls they made, the more the cash register was ringing up a higher number. When he realized how much money it was going to cost to buy these tunes, he freaked and said, “This is insane!” He started swearing away. I was in his office at the time when the lawyer came in and told him that we had a problem.

TT: What happened next?

PZ: Peter turned to me and says, “Well? Whatta you got? You’ve got to fix this.” I asked him what he meant and he said, “We can’t afford these songs. You’ve got to come up with knock-offs. Come up with stuff that sounds exactly like them.”

I told him we were mixing the film the following week and he says, “That’s right.” I said he had at least a half a dozen songs in there and he goes, “That’s right.” I told him, “So you’re giving me five days to come up with six original tunes that sound exactly like these…and fit the same tempo?” He said, “That’s right…what are you still doing here?”

TT: Wasn’t he afraid of lawsuits? TT: Wasn’t he afraid of lawsuits?

PZ: Oh, that was the best one. I went home and I examined closely all these tunes and I thought, these songs have some very distinct sounds. I requested another meeting with his lordship, and I went in and said, “How close do you want me to come to these things?” And do you know what he said?

TT: What?

PZ: He said, “I want you to come close enough that we get sued - but not close enough that they’ll win."

TT: So you had only a week to write and record the songs for Prom Night?

PZ: Yes. The recording part was easy compared to conceptualizing it. How was I going to take “I Will Survive” - in the same number of syllables - and get them all dancing? How was I gonna knock these things off in an effective way?

Once I had figured out how to do that, then it was the process that I described earlier: you write it all out, you call the musicians, book the copyist, book the studio, you come in, get the singers, get the violins, the horns, you mix it, you print it...and you put it on the movie.

But Peter didn’t leave me much time at all because we had a release date at that point. You can only do that stuff when you’re young, because you didn’t get any sleep and you’re running around. Really, it was caused by someone who wasn’t being very competent on the film production side of it.

TT: We wanted to ask you specifically about “Love Me Till I Die.” Horror films can stir up a lot of emotions: fear, suspense, revulsion, for example. But sadness and poignancy are rarely among the feelings these kinds of films evoke. TT: We wanted to ask you specifically about “Love Me Till I Die.” Horror films can stir up a lot of emotions: fear, suspense, revulsion, for example. But sadness and poignancy are rarely among the feelings these kinds of films evoke.

Yet, the scene in Prom Night in which Jamie Lee Curtis’ character discovers that her brother is the killer on the dance floor is very powerful. It’s a beautiful moment in a slasher film and always puts a lump in our throats. Everyone remembers it…

PZ: I did that with my tongue in my cheek. I knew Peter would go for it because with him, there was no room for subtlety. The more you could hit it on the head and on the nose, the more he liked it. I thought it would play properly in the film with the lyrics, given what had just happened in the sequence.

TT: It works very well. It’s memorable. And it’s a combination of the lyrics, the urgency of the song, the editing, and the acting.

PZ: It works well, I agree. It was edited by Brian Ravok and he did an incredible job.

I think for most horror fans, subtlety is not in their vocabulary. (Laughs.) You throw it out the window when you’re doing a horror film. You basically put the pedal down to the floor and you go full speed ahead.

TT: Wasn't the Prom Night soundtrack released in Japan?

PZ: That was a bootleg. All it did was list the tunes off the foreign language track/version. Very poor bootleg quality. The producers didn’t even know about it. PZ: That was a bootleg. All it did was list the tunes off the foreign language track/version. Very poor bootleg quality. The producers didn’t even know about it.

TT: There are two power ballads recorded by Blue Bazar called “Forever” and “All Is Gone.” They’re on the bootleg soundtrack, but not in the film itself. Were those songs meant to be used?

PZ: Yeah, Peter made a deal with that band for like 500 bucks and got the worldwide rights.

TT: But they weren’t used…

PZ: Right, they got cut. There was another song called “Fade To Black”…

TT: The ballad that plays over the final credits.

PZ: Yes. I think that song (the lyrics) is partly credited to Peter Simpson.

TT: There’s a vocalist credited as Gordene Simpson. Who is that?

PZ: That’s his ex-wife.

TT: Does she sing any of the disco songs?

PZ: No, she doesn’t sing any of those. Peter and Gordene were just getting divorced at the time and this was sort of his divorce settlement. PZ: No, she doesn’t sing any of those. Peter and Gordene were just getting divorced at the time and this was sort of his divorce settlement.

TT: Who is singing the disco songs?

PZ: That’s a whole collection of studio singers. If you listen to the songs, they’re not the same singers in all of them.

TT: 1980 marked the beginning of a rapid, undeserved decline in disco’s popularity. While some saw it due in part to the “shallowness” of the music, there was an underlying backlash that was both racist and homophobic. Because disco (in its purest form) had emerged out of the black and gay communities.

Yet history has shown that disco produced some of the most catchy and memorable songs of the era. Any thoughts?

PZ: Yeah, if you go to a club these days...not that I go anymore...they’re still dancing to those songs. That music had something. Maybe the focus was more on melody and lyric. I don’t know WHAT they’re doing today with rap and hip hop…

TT: Disco had a real urgency. And sometimes the best songs of the genre had a melancholy that you don’t see in other types of music.

PZ: Exactly.

TT: Did you spend any time on the set of Prom Night? TT: Did you spend any time on the set of Prom Night?

PZ: Yes. Because it used synch music. They shot that here in Toronto in an old high school, known in the film as Hamilton High. And when I went to the set, that's where I heard those hit songs being played.

I kept shaking my head and saying to the sound mixer who was on the set, “How the hell are you gonna get this off? You’re putting this in the film and they’re dancing and mouthing the words. How are you gonna replace that? He’s not going to get the rights to these songs. These are huge hits.” I knew what was gonna happen, but I couldn’t really do anything about it.

But I was invited down to the set and saw the shoot happening. That was good because it gave me a little bit of a heads up when that fateful day happened that Peter called me into his office and basically said, “Houston, we have a problem.”

TT: Did you meet any of the cast? Jamie Lee?

PZ: Oh yeah. I met them all. You’ve got to remember, Jamie Lee was no big celebrity then. She wasn’t a household name. I found her cold.

I met Eddie Benton and also Casey Stevens, the leading male. These were all struggling actors at the time. In fact, Leslie Nielson did the movie for scale. He didn’t become a big name until the AIRPLANE films. I met Eddie Benton and also Casey Stevens, the leading male. These were all struggling actors at the time. In fact, Leslie Nielson did the movie for scale. He didn’t become a big name until the AIRPLANE films.

TT: You would go on to score the followup sequel Hello Mary Lou: Prom Night II (1987) as well as the two subsequent Prom Night sequels in 1990 and 1992, respectively. What was your favorite (out of all four) to work on?

PZ: I don’t know if I have a favorite. Because if you look at the four of them, they’re all very different from each other.

I mean, Prom Night IV: Deliver Us from Evil really wasn’t like the 1980 original in any way. It was shot in a monastery, it was very sacrilegious. It had that sort of religious undertone to it.

But it was a film that took the horror themes and put them in a monastery, with monks. The whole vibe that goes with that - and the killer in that setting - well, it didn’t relate to the original at all. Yet, it was creepy in its own way.

TT: Related in title only…

PZ: Right. Peter was good at that. He was cashing in on himself.

TT: Let’s talk about 1981’s Ghostkeeper. It has, in our opinion, one of your most interesting and experimental scores. How did that project come about?

PZ: Ghostkeeper was produced by Stan Cole’s brother Harry. Stan had been the film editor who edited Murder by Decree and later, Porky's. That’s how we got called into it. PZ: Ghostkeeper was produced by Stan Cole’s brother Harry. Stan had been the film editor who edited Murder by Decree and later, Porky's. That’s how we got called into it.

I don’t even know if Harry is still alive, but he really didn’t know much about making a movie. So the film was, in many ways, thrown together and assembled by the post-production team: the editors, the sound people, music, etc.

TT: The music to Ghostkeeper has a really sparse feel to it. There’s lots of echo and reverb - and your cues seem to enjoy an uneasy interplay between slight subtle jabs, haunting echoes, and silence.

You also have the sounds of the winter winds that seem to be interplaying with your cues. The overall effect is that it’s organic and very atmospheric. The score adds to the isolation the characters feel in the film’s snowy lodge setting.

PZ: That’s a very good assessment. That’s exactly what it was. A ghost is transparent and very atmospheric. And we tried to put a presence there that wasn’t on the screen. You can’t do that with heavy-handed effects.

The Wendigo wasn't a monster with three heads and fangs. It was something you didn’t really see, so I had to do something, musically, to help the film because none of it was really making any sense. The Wendigo wasn't a monster with three heads and fangs. It was something you didn’t really see, so I had to do something, musically, to help the film because none of it was really making any sense.

TT: It is a creepy movie, however.

PZ: It’s like a lot of films that came out of that era that were just thrown together.

TT: Ghostkeeper has cues that were used in Prom Night.

PZ: Yes. A lot of similar effects were used. I don’t know if the cues were identical. Maybe I used the odd one, I don’t remember.

TT: There’s one particular standout scene, musically. It’s the chase music in the sequence right after Riva Spier has discovered the creature - the Wendigo - in the icehouse…and she’s running from the son of the ghostkeeper through Deer Lodge. It’s great.

PZ: Hmmm. I'd have to see it again. That film was never released.

TT: Never theatrically?

PZ: No.

TT: How long has it been since you’ve seen it?

PZ: I don’t think I saw it after I finished it. Ghostkeeper was a classic tax shelter deal, where the mandate was to finish the film and have it certified. And everybody got their write-off and nobody cared. It never showed up in a theatre and I don’t think I’ve seen it.

I guess somebody years later decided he could make a few shekels here by selling it. I don’t think anyone associated with it made any money. I guess somebody years later decided he could make a few shekels here by selling it. I don’t think anyone associated with it made any money.

To be honest, nobody ever asks me about Ghostkeeper. It’s one of those films that's just kind of forgotten. Not that anybody ever knew about it! It’s pretty obscure.

TT: Well, we’ve championed it for a long time.

PZ: That’s cool.

TT: Thematically, Ghostkeeper shares something with both The Sentinel (1977) and Kubrick's The Shining (1980). Do you recall if either of those pictures inspired you at all, or the filmmakers?

PZ: No, I had never seen The Sentinel or The Shining when I did Ghostkeeper.

TT: Let’s talk about your score for My Bloody Valentine. The music there is much different than your scores for either Prom Night or Ghostkeeper. How did you get that gig?

PZ: I was hired by the producers, John Dunning and André Link. They were based in Montreal and were doing tax shelter deals left, right and center. They owned Cinépix, which in turn became CFP.

And then CFP was bought by Lion’s Gate, which is what we know today. They have the original Dunning and Link library. So Lion’s Gate is the successor to those two guys who started by actually making porno movies back in the ‘60s. (Laughs.)

I was the new kid on the block and was called in from Toronto to Montreal - which is about a 45 minute flight - and they said, “We wanna talk to you.” We made the deal on My Bloody Valentine, and John and André very much called the shots.

Director George Mihalka went down into the mine and shot the damn thing and basically, I never saw him. I was above the earth the entire time! (Laughs.)

TT: My Bloody Valentine has a more conventional score. You’ve spoken about wanting to create a different kind of musical motif for each of the individual murders. Correct?

PZ: Yes. If you look at it, none of characters were killed the same way. One was burned to a crisp in a clothes dryer. Another one had a shower head stuck through her neck and out her mouth. These were all very unique ways to kill someone, and I thought, if you’re gonna do that, then we should have a unique score to go along with that.

TT: The opening credit music is very nice. It has a wet, drippy, dank kind of feeling to it that is clearly trying to mimic the mine setting itself.

PZ: Exactly. That was a case where you go with the picture, let it drive the music in a way. You’ve got this damp, wet, cold mine. So you put damp, wet, cold music. The guy’s got this mask on, and it’s creepy, yet erotic, and everything else.

Like in any horror film, there are times when you go with it, and there are times when you play against it.

TT: In a way, My Bloody Valentine was a success before it came out. After the MPAA demanded all those gore cuts prior to its release, you all must have been clued in to the fact that you had hit the mark while filming this bloody and graphic horror film, that you had the next hit slasher on your hands. TT: In a way, My Bloody Valentine was a success before it came out. After the MPAA demanded all those gore cuts prior to its release, you all must have been clued in to the fact that you had hit the mark while filming this bloody and graphic horror film, that you had the next hit slasher on your hands.

PZ: Oh, it was so cut. I mean, it was very, very graphic. Even the uncut version that was re-released recently is still nowhere near what Mihalka originally turned in.

TT: He’s said there is additional footage that was just never found.

PZ: That’s right. And I know it because I had to score to it. Some of it I couldn’t even watch. It was out there.

TT: Do you remember anything particularly graphic that was never recovered?

PZ: There wasn’t a whole scene that never made it, for example. It would be like if you expanded the sequences that are already there. Even with the restored footage back in place, the first version was still much more graphic, and there were more close-ups and there was more gratuitous violence. Just expand what’s there.

TT: Tell us about the end song, “The Ballad of Harry Warden” sung by John McDermott. It’s terrific. What’s your memory of writing that?

PZ: Again, that was a bit of a Peter Simpson “retake.” I got called in. You gotta remember, Dunning and Link were businessmen. They had this picture that was coming out. It was a Paramount release. And they had a great title. It was a unique idea. You can’t miss.

So they wanted to put a hit song on there that would sell a bizillion records. The thinking from a film producer’s point of view is that the record is going to sell the movie. And the thinking from the record label is that the movie is going to sell records. It’s one of those things where both companies think the other is gonna make them rich. So they wanted to put a hit song on there that would sell a bizillion records. The thinking from a film producer’s point of view is that the record is going to sell the movie. And the thinking from the record label is that the movie is going to sell records. It’s one of those things where both companies think the other is gonna make them rich.

TT: Did they think “The Ballad of Harry Warden” was going to be a single?

PZ: Well, no. They had no money left. I forget the song they actually wanted to buy. They told me they had no money so it fell back on my contractual obligation. They said I had to come up with something and I asked them what they wanted. All I got was, “We don’t know what we want. You think of something.”

TT: So they originally wanted to insert a known hit record into the film?

PZ: Yeah. Some song that was out at the time. It had NOTHING to do with the movie.

TT: Was it a folk kind of song?

PZ: No, a rock song. They do that. They put some song at the end that has nothing to do with what you just watched for the last 90 minutes.

So I had an idea. What if we had this ballad that sort of created this recap of what we just experienced? And it was like the folklore would live on in this mythical town where this Harry Warden was almost canonized in a way. He was made into some kind of celebrity even though he was rotten.

Maybe you’d sit back and listen to this recap, and it’s almost sad. Like it’s too bad what happened to this little town. And he lives on. Harry Warden is still alive and he’s out there. And if there’s a sequel, he could come back.

TT: The Gaelic influence in it is wonderful. And it has a touch of The Wicker Man too.

The idea of an end ballad for My Bloody Valentine is one of the first of its kind for a horror film, in a way. Several horror films after that would utilize a kind of folksy ballad - either in the opening or closing credits - which essentially laid out or recapped the plot. Madman (1982) and Sweet Sixteen (1982) come to mind... The idea of an end ballad for My Bloody Valentine is one of the first of its kind for a horror film, in a way. Several horror films after that would utilize a kind of folksy ballad - either in the opening or closing credits - which essentially laid out or recapped the plot. Madman (1982) and Sweet Sixteen (1982) come to mind...

PZ: And movies today don’t do that. They don’t let you sit back and replay what you just saw. Nowadays, they don’t let you catch your breath and think about it.

I do remember Dunning saying back then, that it didn’t matter because everybody leaves the theatre as soon as the credits come on anyway. That was the conventional wisdom. It doesn’t matter what’s on there. This is just sound for the credit crawl, etc. And I thought, it kind of does matter because the film ends and leaves you a little startled when you see who the actual killer was. His name was Axel, he killed them with an Ax. I mean, how subtle is that?

TT: And most startling about it is the open-endedness of the whole thing. Contrary to what Dunning believed, people remember that song.

PZ: Well, they remember the song because I kind of made them remember it. I didn’t just stick some unrelated country song on there that didn’t mean anything.

TT: Speaking of country songs, are you responsible for the ones that are played in the bar and party settings?

PZ: I wrote them. Most of them anyway. I think there were one or two that were licensed for like 100 bucks.

TT: One of them sounds like a Dolly Parton rip-off. It’s great…

PZ: Yeah, it is a Dolly Parton rip. She was just coming into fame then.

TT: She was huge at that point.

PZ: No pun intended!

It’s funny, I just made a CD of “The Ballad of Harry Warden” and sent it off to Quentin Tarantino in L.A. because I had gotten an email from Eli Roth, the actor in Inglorious Basterds.

He wrote that My Bloody Valentine is one of Quentin’s favorite slashers. He told me, “We go to Quentin's house and wind down the DVD to that song, and we all know the lyrics by heart and sing along to it.” He wrote that My Bloody Valentine is one of Quentin’s favorite slashers. He told me, “We go to Quentin's house and wind down the DVD to that song, and we all know the lyrics by heart and sing along to it.”

TT: Any parting thoughts about My Bloody Valentine?

PZ: Just that I recently went to a big screening of the film. It was reunion with some of the cast. Lori Hallier, who still looks pretty damn good. Mihalka was there. Neil Affleck, who played Axel, took part.

The theatre was full. It was standing room only. And every time somebody got killed or a pick ax went through someone’s forehead, they all stood up and started cheering and clapping…

TT: Horror fans. We're a classy bunch.

PZ: (Laughs.) Yeah, really! But I was thinking how much they just loved it.

TT: Very well directed.

PZ: It is well directed. It’s all well done. Nicely edited…

TT: The film works because it took the slasher genre into a real working class environment.

PZ: It was a unique idea. Mihalka was telling me, you try bringing a seventy five man crew down below the earth in an elevator that took fifteen minutes just to get down. They didn’t have CGI. They didn’t have any of that. They had to bring all that stuff down there and set it up and light it and shoot it.

Not to mention, the danger aspect of it.

|